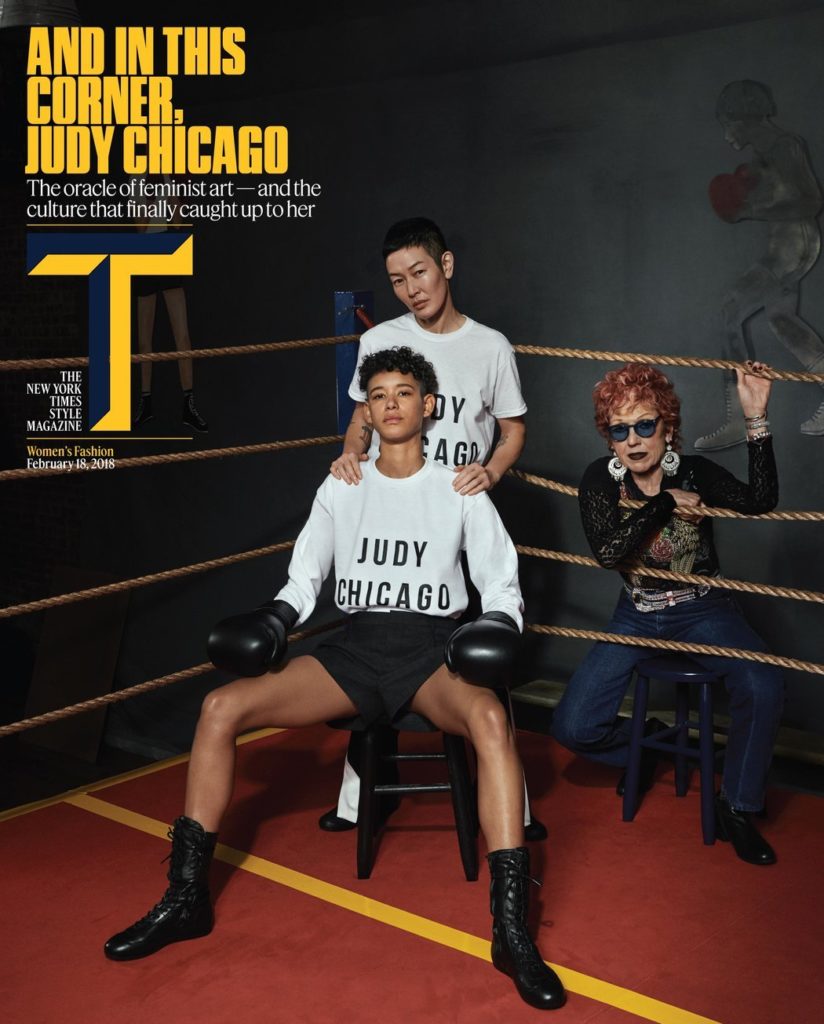

Since 2018, Hanya Yanagihara has been the Editor in Chief of “T” magazine, the style magazine of the “New York Times”. During her tenure, the magazine has supported diversity of both its content and its models, something that I have really admired. In Hanya’s first cover story on February 18, 2018, she reprised my 1971 Boxing Ring Ad, positioning me as the ringside manager with two models sporting boxing gloves and “Judy Chicago” t-shirts. Recently, “T” magazine included me again for the April 24, 2022 issue which was devoted to the “Creative Life”. Here is my “advice to a late-career artist” along with the other articles in which I appeared – with many thanks to Hanya and also, Thessaley La Force, a Features Director. In addition to their ‘day jobs’, both Hanya and Thessaley are serious authors.

Interview by Thessaly La Force | April 24, 2022

I often say, “I don’t want to be the Ann Landers of the art world.” I learned how to be an artist by looking at my predecessors. This year, I’m revisiting the installation of “Womanhouse,” which I first facilitated in 1972. It’s being recast as “Wo/Manhouse 2022” as a way of offering young New Mexico artists across the gender spectrum the experience of making meaningful art. Because of this, you might say I’m enacting advice to other artists.

Many women artists of my generation became bitter because of a lack of deserved recognition. But I’m not bitter, perhaps because I have a global perspective that makes me understand how fortunate and privileged I’ve been in comparison to millions of women around the world.

I’m happy about the fact that success has come late in my career because that meant that I had five decades of uninterrupted art making without ever having to think about the market. I’m all about creating art that means something; I’m not about the market. It’s particularly dangerous now for young artists because they get gobbled up by the business, spit out and then they’re done. What I did — and this wasn’t so much about that as it was about the straight-up rejection of my work by the system; “The Dinner Party” (1974-79) being a piece that everybody wanted to see and nobody wanted to show — was, I made working in my studio my reward. I had a burning desire to be an artist from the time I was a child. After all, who defines what’s good? You have to decide for yourself. I had the support of those who really believed in me, and that’s important — you need people you trust to give you feedback. The art world never supported me. It was the opposite. It tried to kill me.

By Alice Cavanagh | January 20, 2020

“I’m 40 years past ‘The Dinner Party’,” she says of her monumental 1974-79 work, a 48-foot-wide ceremonial banquet scene that celebrates 39 female icons, from the ancient poet Sappho to the artist Georgia O’Keeffe, and was produced in collaboration with a cohort of textile and ceramic artisans. “But the issue of changing attitudes toward women and imagining ‘the female divine’ is something that hasn’t happened yet, has it?”

By Thessaly La Force | August 5, 2019

Chicago does not intend to be erased, the way many of the women she discovered in researching “The Dinner Party” were. Chicago saw how women artists of her generation were never allowed the same sense of permanence as men, to consider their future on any grand scale. She recalled a recent gathering of her contemporaries at an art opening: “One of them stood up and she said, ‘I’m going to be in my 90s. What’s going to happen to my art?’” As important as the work itself is Chicago’s refusal to let it and any understanding of its creation disappear.

By Thessaly La Force | February 18, 2018

On the Cover: Judy Chicago is featured in T’s Feb. 18 Women’s Fashion issue. Photograph by Collier Schorr. Styled by Suzanne Koller

For this issue’s Cover, T wanted to put Chicago back in the ring – or rather, just outside of it; she is more of the coach now, a leader whose work has been steadily recognized through the years in mainstream and intuitional art circles. In the ring are Jenny Shimizu and Dilone, models who have, in their own ways, been a force for change and diversity in the world of fashion. The eye is drawn to Chicago, though, who, in this portrait by New York-based photographer ang frequent T contributor Collier Schorr, has emerged from the battle of the sexes – isolated, yes, and at moments frustrated- but also victorious.

By Sasha Weiss | February 18, 2018

Judy Chicago, Installation view of Wing Two, featuring Elizabeth R., Artemisia Gentileschi, and Anna van Schurman place settings from The Dinner Party, 1979, Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, Collection of the Brooklyn Museum. © Judy Chicago/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York Photo © Donald Woodman/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

IN A LARGE, low-lit room is a triangle-shaped table arranged with 39 place settings, the site of a distinguished gathering. It is laid with plates that rise a few inches off the table, as if levitating, each one sumptuously painted with wings or petals or licks of flame emanating from a glowing center: variations on the vulva. As you move along the table, which is 48 feet long on each side, the plates become small sculptures, bulbous and gleaming. Beneath them are runners embroidered with elaborate designs and names in gold thread — women of accomplishment who are familiar and unfamiliar, mythical and rarely spoken of: Sappho, the ancient poet; Anna Maria van Schurman, the 17th-century artist, thinker and theologian; Elizabeth Blackwell, the first female physician in the United States. The whole assemblage stands on a floor of luminescent triangular tiles covered in more gold — 999 names of other heroic women written in curling letters. The room is like a temple — a holy place, distinct from the everyday…